Government must do more than get out of the way if India's rise is to continue

India Grows at Night: A Liberal Case for a Strong State, by Gurcharan Das, Allen Lane, RRP£19.99/Penguin Global, RRP$25, 320 pages

Twelve years ago, Gurcharan Das was first out of the blocks to declare India a rising economic power. In India Unbound(2000), Das rightly attributed the country's buoyancy to the dismantling of the "licence Raj" – the uncompleted project begun in 1991 by Manmohan Singh, India's then finance minister. The retreat of a tentacular state had enabled a dynamic private sector to emerge and put an end to India's "export pessimism", he wrote. The country's software companies thrived only because New Delhi had never set up a department for IT.

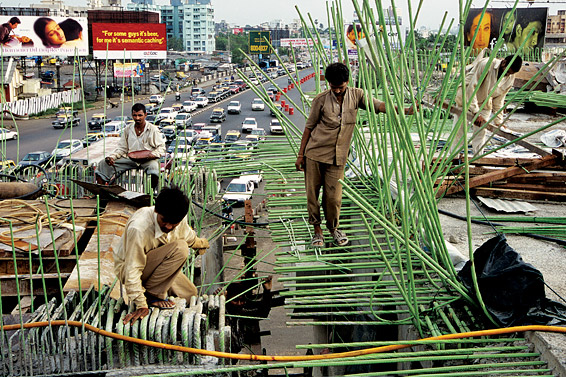

Das's thesis remains just as persuasive today. But at a stage where even the optimists are worried about what is behind India's economic slowdown – growth has almost halved in the past two years to about 5 per cent – he now believes India Unbound told only part of the story. India continues to need a less meddlesome government, he argues in India Grows at Night. Forty per cent of the country's listed company profits come from public entities, many of which are unregulated monopolies. And the Indian state remains as venal as ever. It still requires 118 permits – or "corruption opportunities", in Das's words – to get a licence to build a power station. No wonder a third of the country still lives in darkness.

Simply calling for less government is no answer, says Das. It needs also to be strong. During a period when the rest of India has been in ferment, India's state has undergone only mild tinkering. As Singh has discovered, latterly as prime minister, even tepid administrative reform gets sabotaged. The country's growing cadre of Fortune 500 billionaires may be putting India on the global map. But most of them are neither equipped, nor inclined, to provide running water to the slums or power lines to the villages. Nor, it seems, is the state. In the memorable description of Harvard's Lant Pritchett, India's state is neither strong nor failing but "flailing". Indian capitalism needs an honest referee. And the hundreds of millions of Indians who live on less than $2 a day are in desperate need of a hand up rather than a hand out (as the saying goes). At times, Das's shift of emphasis seems more like a change of mind. His book, which he describes as a "moral essay" in the spirit of London's 18th-century pamphleteers, is a far cry from the libertarianism of Robert Nozick, the Harvard philosopher who championed the minimalist state and who taught and influenced Das. If Nozick was the guiding spirit behind India Unbound, Das's latest book is inspired more by John Rawls and Amartya Sen. Most Scandinavian states, he writes approvingly, "have the capacity to manage a large welfare state extraordinarily well while remaining strong and liberal." Alas, these kinds of institutions do not grow on banyan trees.

Das's core argument is right and urgent. While the 23-year-old student gang-raped on a New Delhi bus last month lay dying from her injuries on a busy road, the police were arguing over which district had jurisdiction. They paid no heed to her boyfriend's pleas to first take her to hospital. She was left there for 45 minutes. To ignore the spilled guts of a dying woman while indulging in a petty turf battle takes a special callousness; it also speaks of a dysfunction at the heart of Indian public service. Reforming the state is no easy business. As Sheila Dikshit, New Delhi's chief minister, has argued, the answer is "not to fix the pipes but to fix the institutions that fix the pipes". She was talking about Delhi's water board, which has 20,000 unsackable employees.

Das places many of his hopes on reviving dharma, an ancient Hindu concept of the good society that loosely translates as right action, or reciprocal altruism. Something of a polymath, Das's grasp of the intricate moral underpinnings of the Mahabharata is impressive – and instructive. But at times they seem far removed from the messy sociological entanglements of India's reality. "Some nations possess a code word which, like a key, unlocks their secrets," he writes. "That word is liberty in America's case, egalité in the case of France: for India it is dharma." In my view India's key is plurality. But this is a minor quibble.

Das has written a timely book that deserves to be widely read. And it has its share of hard-headed proposals – for example, courts should be required to accelerate criminal cases against elected politicians rather than put them in abeyance as they do now (which is why so many crooks want to sit in parliament). He endorses an ingenious idea from Kaushik Basu, now the World Bank's chief economist, to give bribe-givers legal immunity so they can blow the whistle on bribe-takers. So too are his ideas to screen out small parties – with 177 parties in total India's politics is inherently fractious. And so on. As Das is also at pains to point out, India has much to celebrate nowadays. It also faces a cacophony of institutional challenges. "The truth is that the Indian bureaucracy is not the kind that can propel India to the next level as a global power," he writes. It is hard to disagree.

Edward Luce, the FT's chief US commentator, is a former New Delhi bureau chief and author of 'In Spite of the Gods: The Strange Rise of Modern India' (Abacus)